On October 25, 2017, a new political party was formed in Turkey, taking the name İyi Parti (Good Party).

This new party was founded by Meral Akşener, a vocal Turkish politician and critic of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Akşener, who has been in politics since the mid-1990s, once belonged to the True Path Party, a secular conservative party. As the True Path Party faded into the background, she then joined the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), a small but influential far-right nationalist party which, despite its more moderated image today, has a history of violence.

Last year, as the MHP cozied up to Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his Islamist Justice and Development Party (AKP), Akşener attempted to oust party leader Devlet Bahceli from his post. She was unsuccessful and forced out of the party.

During Turkey’s recent constitutional referendum, the MHP was split. While much of the high-level party officials were supportive of the proposed transition from parliamentary to presidential democracy, many of the party’s voters were not. Indeed, when Turks went to the polls, large amounts of voters in the MHP’s regional strongholds in the south of the country voted against the transition. Akşener was one of many voices to express her opposition to the referendum.

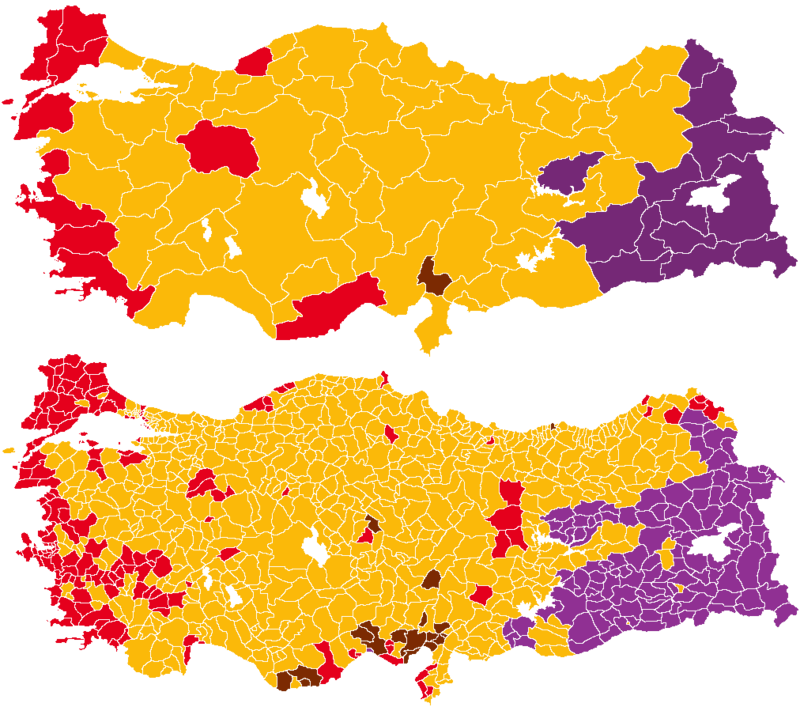

Maps detailing the results of the Turkish elections in June 2015 and the referendum results. Brown areas in the map on the left are areas won by MHP, many of which are red ("No" voting in the referendum).

Despite the split, the referendum still narrowly passed and Turkey is undergoing the transition from parliamentary to presidential which its critics dismiss as a power grab by President Erdoğan.

Akşener decided this autumn to start a new party, with one seemingly clear goal in mind: to run for president, unseat Erdoğan and pick up the damaged pieces of Turkey’s still-intact but fragile secular democracy in hopes of gluing them back together. The next Turkish General Election is in November 2019, giving Aksener two years to craft her party's platform, reach out to the Turkish people, and fight the AKP.

From an ideological perspective, the İyi Party claims to be centrist, perhaps slightly leaning right in an attempt to woo wary AKP supporters. Like the CHP, it is nationalist, secular, and Kemalist, and it also has taken up a bit of populist anti-establishment sentiment as a response to what it perceives as the ineffectiveness and polarization brought on by the establishment Turkish political parties. It also seeks to reverse the transition from presidential to parliamentary democracy.

From an ideological perspective, the İyi Party claims to be centrist, perhaps slightly leaning right in an attempt to woo wary AKP supporters. Like the CHP, it is nationalist, secular, and Kemalist, and it also has taken up a bit of populist anti-establishment sentiment as a response to what it perceives as the ineffectiveness and polarization brought on by the establishment Turkish political parties. It also seeks to reverse the transition from presidential to parliamentary democracy.

A Gezici poll in mid-October had Erdoğan winning another term as president with 48% of the vote. Ms.Akşener sat 10 points behind him at 38%. In third place was Kemal Kilicdaroglu, leader of the Kemalist center-left Republican People’s Party (CHP) with 14% of the vote. In this scenario, Akşener and Erdoğan would go to a runoff election which she would have a good chance of winning considering most CHP voters' fierce opposition to the President.

In Turkey’s last direct presidential election, the CHP and MHP rallied together behind Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu, but he came in second with only 38% of the vote compared to Erdoğan’s 51%. Because Erdoğan won over 50% of the vote, no runoff election was necessary. Selahattin Demirtaş, a Kurdish politician from the People’s Democratic Party (HDP) came in a very distant third with 10% of the vote.

President Erdoğan has many critics in Turkey. However, his critics come from vastly different political angles and rarely do they agree on a consensus. The Republican People's Party, known by its Turkish initials CHP, the second largest party in Turkey, is a secular center-left party. While it enjoys large popularity on Turkey's western coast and in cities like Istanbul, Ankara, and Izmir, its support quickly dissolves once you delve further into the Turkish heartlands. The MHP, already in a state of crisis between the pro- and anti-Erdoğan factions, only tends to draw large support from a small region in Turkey's south. The Kurdish-interest HDP receives almost no support outside the southeast of the country. MHP and HDP refuse to speak to each other and CHP seems stagnant in terms of how much support they can amass. None of these parties seem to be able to cut substantially into Erdoğan's base of support, which even in its low point in the June 2015 elections managed 40% of the vote, still 15% higher than that of the second-place CHP.

The new presidential system Turkey is moving towards may work in the Good Party's favor, but a few things will need to happen for them to actually unseat Erodgan and the AKP.

In order for Akşener to win, she's going to need to master a big-tent appeal. First, she must be able to convince the CHP and MHP to rally behind her as one as they did behind İhsanoğlu in 2014. It seems unlikely that the second largest party in Turkey will not nominate their own candidate for this position, but Akşener could broaden her appeal and call for her Good Party and the CHP to join forces. If the CHP is dead-set on running their own candidate against her such as Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, it will only split the anti-Erdoğan voting bloc into smaller pieces. Kılıçdaroğlu, the current leader of the CHP, has said he is not interested in running for President in 2019, but that does not necessarily mean the party will not field a candidate.

Calling MHP to her cause may be even more difficult as she

is an ex-member of the party. The pro-Erdoğan faction of the MHP may try to scuttle her plans to win the presidency by

running a token candidate who is only lukewarmly opposed to Erdoğan. While Akşener looks like she is already drawing MHP voters to the İyi Party, uniting

the party to the point that MHP does not run their own candidate will be difficult.

A Sonar poll conducted between November 1 and 6 has MHP's support dwindling down to 7.8% while the İyi Party is on track to gain 21% of the vote for the Parliamentary election. In Turkey, a political party must gain at least 10% of the vote to gain parliamentary representation. If this poll is accurate, MHP would lose all its representation at the national level.

A Sonar poll conducted between November 1 and 6 has MHP's support dwindling down to 7.8% while the İyi Party is on track to gain 21% of the vote for the Parliamentary election. In Turkey, a political party must gain at least 10% of the vote to gain parliamentary representation. If this poll is accurate, MHP would lose all its representation at the national level.

Akşener’s ability to appeal to HDP and AKP voters may be

most difficult of all. As a former member of the far-right nationalist MHP, Akşener once carried a banner that Kurds living in Turkey have severe

reservations about. Considering both co-leaders of the HDP, Selahattin Demirtaş and Figen Yüksekdağ are under arrest, neither of them may run in the

presidential election and it is unclear whether HDP will even be allowed to

contest any part of the 2019 elections. It is unlikely the Kurds will remain

politically silent in 2019, and the June 2015 elections showed they can be a

considerable force in Turkish elections when they won 13% of the vote. Considering MHP and HDP have barely been on speaking terms while in Parliament together, voters who flip from HDP to the

The other goal in Akşener's quest to oust Erdoğan from power is to cut into the base that Erdoğan has relied on 15 years. Erdoğan first swept to power in 2002, and has won elections consistently since then in 2007, 2011, twice in 2015, and then 2017's referendum.

As stated before, even in the June 2015 election when AKP slumped to its worst result since its founding in 2001, it still managed to capture just over 40% of the vote. If Akşener can't cut into this base without significant support from other anti-Erdoğan factions, it will be difficult for her to accomplish her speculated goal of unseating the President.

Most of the support for Akşener seems to be coming from disaffected MHP voters, as some polls have the MHP falling from its last performance of 11.9% down to around 3-5%, which would effectively end its time in the Grand National Assembly as parties need at least 10% of the vote to get represented. In polls where the İyi Party gets over 10% of the vote, AKP slumps to around 38-40%, while CHP and HDP's percentages stay mostly the same.

Take a Sonar poll conducted from November 1-6. Its results (AKP 38.5%, CHP 23.5%, MHP 7.8%, HDP 10.3%, İyi 16.1%) indicate that CHP and İyi would have a slight advantage in voting percentage (39.6% to 38.5) to scrape out a tiny majority over the AKP's plurality. If they focus on anti-Erdoğan sentiment, these two parties could likely stall much of Erdoğan's agenda even if he still won the Presidency. The direct presidential poll conducted by Gezici in mid-October suggested that Akşener may be popular enough to, at the very least, force Erdoğan into a runoff election for the Turkish Presidency, which she would make extremely competitive if the CHP voters rally behind her.

Of course, all of this is speculation. Polling is far from an exact science, and the İyi Party is still in its infancy. How much appeal it truly has or can muster when it's time for Turks to go to the polls in 2019 is still uncertain. Their daring attempt to unseat President Erdoğan has a path to victory, but it's a long road ahead.